You might be wondering—while jute bags, cotton clothes, or paper are biodegradable, why do plastics stick around for so long even though they're made from a somewhat natural product like oil?

Why doesn’t plastic degrade in the environment like a banana peel?

Well, here's the scoop: it's because plastic is basically the new kid on the block in Earth's history!

Think about it—plastics made from oil are barely a century old. One of the most commonly used plastics – Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – strutted onto the scene in the 1940s, and it's been causing a ruckus ever since. It is a type of plastic commonly used in the production of beverage bottles, food containers, and other packaging materials. Known for its clarity, strength, and recyclability. PET is among the most widely used types of plastic globally,

Now, you might be thinking, “And why is this a problem?”

Here's the deal: when stuff breaks down in nature—like a banana peel or a piece of paper—it's usually because of tiny powerhouses called microbes.

Microbes have been honing their craft for billions of years, chomping on anything they can get their hands on to derive energy for survival, whether it is animal flesh or any kind of plant product. And they do this with the help of enzymes that they produce.

Plastics made from oil are still alien to these microbes. They're still scratching their heads, wondering what to make of these shiny, synthetic invaders. Can they munch on them? What are they even made of?

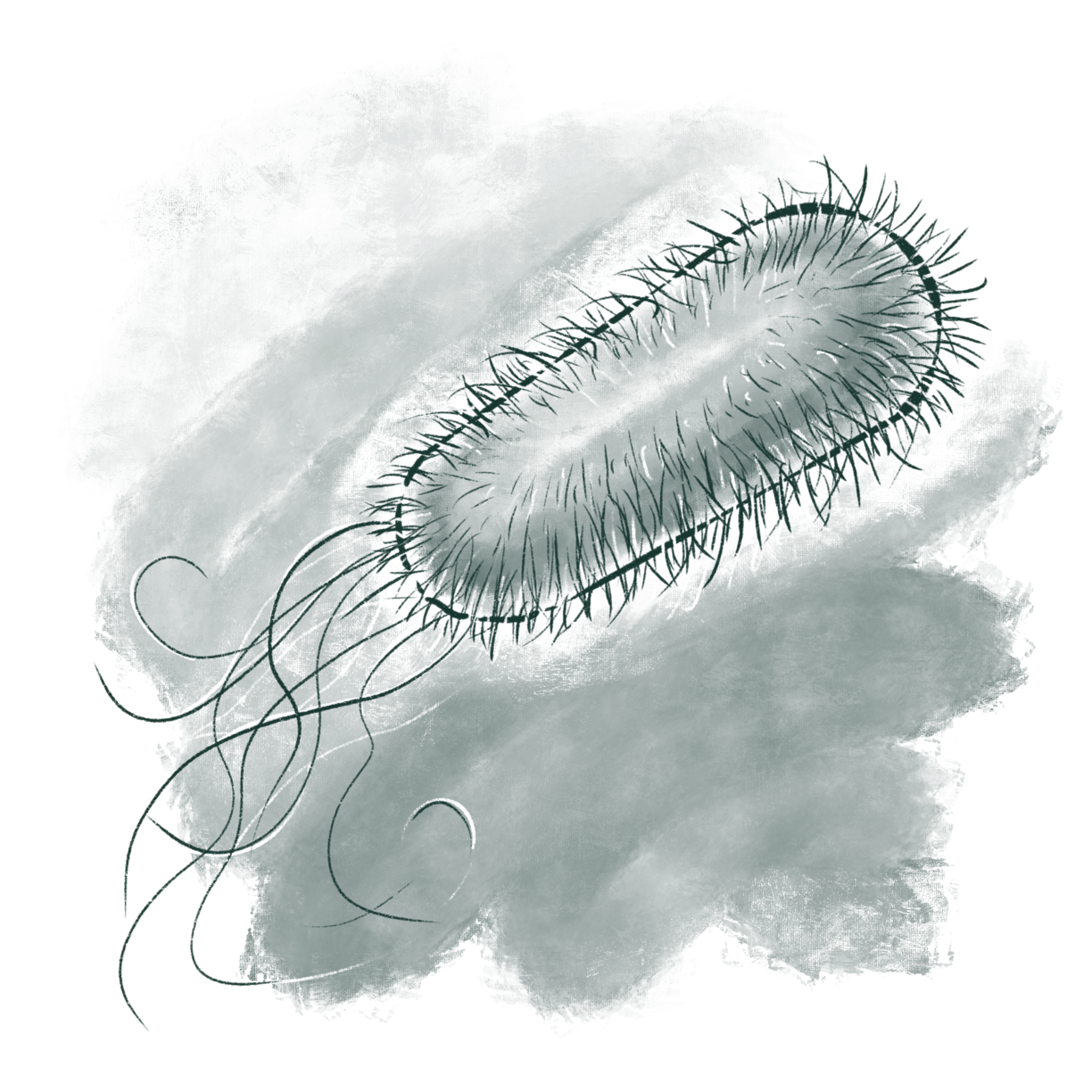

But wait, here's where the story takes a wild turn: Enter the bacteria Ideonella sakaiensis - the rebel of the microbial world.

While everyone else is still trying to figure out plastics, this bacterium is like, "Challenge accepted!" It evolved to feast on plastics like a champ, pushing the boundaries of the "survival of the fittest" game more than any other living organism.

Bacteria that chomp on plastic

In 2016, a team of Japanese researchers from Kyoto Institute of Technology and Keio University made a revolutionary discovery. In the samples they collected from a plastic recycling plant in Sakai City, Japan, they stumbled upon something extraordinary – Ideonella sakaiensis.

This little marvel eats plastic and survives on plastic. But what's even more remarkable is how it devours one of the most produced plastics in the world: PET, which finds common use as plastic water bottles. PET when made into threads is commonly known as “polyester” which you might know, is used for making clothes. It's tough, durable, and notoriously resistant to degradation. Yet, here's Ideonella sakaiensis, chomping away at PET like it's no big deal.

The discovery of this plastic-eating bacterium sent shockwaves through the scientific community. Suddenly, the seemingly insurmountable problem of plastic pollution doesn't seem so daunting anymore.

With the discovery of Ideonella sakaiensis, the scientific community buzzed with excitement and anticipation. It sparked a wave of public interest and media attention.

As researchers around the world scramble to unravel the mysteries of Ideonella sakaiensis, one thing becomes clear: nature never ceases to amaze us. In the battle against plastic waste, it seems Mother Nature has a few tricks up her sleeve after all.

How do bacteria break down plastics?

These enzymes, known as PETase and MHETase, proved to be potent weapons in the fight against plastic waste.

But what do these enzymes do exactly? How do they degrade plastic?

Imagine a big sandwich with layers of bread, meat, and cheese. If you place this sandwich near a colony of hungry ants, what do you think will happen? Within a few hours, the entire sandwich disappears!

In this scenario, the ants symbolize plastic-eating bacteria. Initially, the sandwich might appear too substantial for the ants to tackle, much like PET seems indestructible to regular bacteria.

However, ants possess powerful strong teeth that enable them to swiftly cut through the sandwich layers. Gradually, they begin to nibble away at the sandwich, breaking it down into smaller pieces. With each bite, the ants reduce the sandwich into crumbs, which they transport back to their colony. Eventually, only a pile of crumbs – if anything - remains on the ground.

As we’ve learned, plastics are created from oil by linking monomers together to form long chains known as polymers. Plastic-eating bacteria produce enzymes like PETase and MHETase, which function similarly to the powerful mandibles of ants. These enzymes work tirelessly to break down the polymers in PET plastic into individual, smaller monomers.

Just as ants survive by consuming the small, chopped-up pieces of the sandwich, plastic-eating bacteria derive energy to survive by breaking down the polymers in plastic and eating the small monomers.